Episode 15, "Circe," takes place around midnight (one schema

has it ending at 12 AM, the other starting then). It is the

witching hour. At the outset there are echoes of Goethe's

Walpurgisnacht and Flaubert's vision-tormented St. Anthony.

Later, Homer's story of an enchantress turning men into

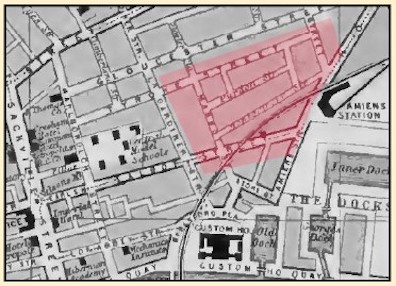

animals dominates. The scene is what Dubliners of Joyce's time

called the Monto—a large, poor, and dangerous red-light

district east of O'Connell Street. After the seemingly

chaotic, reality-bending proliferation of narrative voices in

Oxen of the Sun, Circe offers a series of wildly

dramatic scenes, some of them more or less actual, others

clearly hallucinatory. It is not always easy to tell the

difference, or to say who may be hallucinating. The chapter is

not difficult to read, as Oxen was, but it perpetuates

Oxen's kaleidoscopic variety and its assault on

traditional narration—the action being presented now as

dramatic dialogue with stage directions. Astonishing effects

share the stage: quasi-Freudian psychoanalysis (minus the

analyst), hilarious comedy, matter-of-fact sex changes,

nightmarish apparitions, grandiose wish-fulfillments and

public disgraces. On every page—and there are many, filling

nearly a quarter of the novel—phrases and preoccupations from

earlier chapters reappear, creating a sense that all of June

16 is being recycled, tumbling about in a vast phantasmagoric

washing machine.

Book 10 of the Odyssey tells how men sent out to

investigate a palace on a strange island find, as they

approach, mountain wolves and lions who act like friendly

dogs. The goddess Circe invites the men into her home and

gives them a drugged drink that turns them into pigs.

Eurylochus, who has suspiciously remained outside, runs back

to tell the others, and Odysseus goes to rescue his men. On

the way, the god Hermes warns him not to attack Circe but to

accept her offer of a drink, because a plant called moly will

counteract its effect. Odysseus accepts the plant from Hermes

and does as he advises, entering the house, drinking the

potion, threatening Circe when she thinks to enchant him, and

agreeing to her suggestion that they have sex, but only after

extracting a promise "that she will not plot further harm for

you— / or while you have your clothes off, she may hurt you, /

unmanning you" (299-301, trans. Wilson). After this

trust-building exercise, Odysseus persuades her to free his

men. He goes back to his ship and, over Eurylochus's

objection, leads the rest of the crew to the dreaded palace,

where for one year all the men feast and drink and recuperate.

Crucial elements of this story make it into Joyce's chapter.

Animal images are everywhere in Circe, and sometimes

there are clear echoes of the Greeks turning into beasts.

Perhaps the most overt comes when Zoe beckons Bloom into Bella

Cohen's brothel:

(He hesitates amid scents, music, temptations.

She leads him towards the steps, drawing him by the odour of

her armpits, the vice of her painted eyes, the rustle of her

slip in whose sinuous folds lurks the lion reek of all the

male brutes that have possessed her.)

THE MALE BRUTES

(Exhaling sulphur of rut and dung and ramping in their

loosebox, faintly roaring, their drugged heads swaying to

and fro.) Good!

Like Odysseus going in to rescue his men, Bloom goes in after

Stephen, whom he has followed from Holles Street. Inside, he

is repeatedly threatened with "unmanning," most violently when

he becomes an enslaved, degraded female prostitute at the

mercy of the aggressive Bello. Bloom's eventual recovery of

sobriety, fortitude, and masculine agency recall Odysseus's

escape from danger. At the end of the chapter he heroically

rescues Stephen from exploitation and violence and leads him

away from the nightmarish district.

Many other literary works featuring hallucinatory magic,

dramatic hyperrealism, and perilous sexuality inform the

matter and manner of Joyce's chapter. A footnote in Gifford's

volume of annotations supplies a partial list: Flaubert's The

Temptation of Saint Anthony; Goethe's Faust;

Hauptmann's The Assumption of Hannele; Ibsen's Ghosts;

Strindberg's The Ghost Sonata and The Dream Play;

Sacher-Masoch's Venus in Furs; Krafft-Ebing's Psychopathia

Sexualis. Havelock Ellis's Studies in the Psychology

of Sex almost certainly belongs on this list.

Circe represents the fulfillment of one of Joyce's

most cherished aesthetic ideas: that literary art achieves its

most profound effects in drama. In the early essay "Drama and

Life" (1900) he explored the notion that great dramatic works

get at the most enduring truths of human existence. In part 5

of A Portrait of the Artist (1904-16) he had Stephen

Dedalus elevate drama over lyric and epic by observing that

the dramatic artist transcends his own emotional states,

projecting his personality so self-effacingly into his

characters that they take on "a proper and intangible esthetic

life." In Exiles (1914-18) he produced an Ibsen-like

stage play incorporating some of the concerns that would

dominate Ulysses. In Scylla and Charybdis

(1919) he had Stephen discuss Shakespeare as the archetypal

literary creator. Circe (1920-21) can be seen as the

fruition of all these years of thinking about drama as a

vehicle for high literary aspirations. It is a spectacular

achievement.

Readers can discover other features of this stunning closet

drama on their own, but one final introductory observation may

be helpful. At many points in Ulysses the phrase "a

retrospective arrangement" recurs. Among other applications,

the expression seems relevant to the way most chapters in the

book build upon, and require precise recall of, earlier ones,

explicitly alluding to things mentioned much earlier and

forcing readers to remember when they first heard them. Circe

takes this practice to dizzying extremes. For its best

students, it offers a kind of comprehensive final exam:

underline every phrase on page 1 that you have encountered

elsewhere in the novel; in the margin, identify the chapter in

which each occurs and describe the context and significance;

repeat for the next 180 pages.

In their brief introduction to the chapter, Slote, Mamigonian,

and Turner quote John Rickard's response to this feature of

Circe:

"virtually every notable occurrence, every word of significance

in Ulysses is 'remembered' by the text and becomes available to

the characters—not only to the character who originally

experienced the event, but [also] to other characters and to the

various, often limited, narrative voices in the novel. Thus, the

text of

Ulysses becomes a sort of Akasic memory 'of all

that ever anywhere wherever was'" (

Joyce's Book of Memory,

108). Rickard offers the analogy of Akasic memory in the

speculative, guarded spirit appropriate to all discussions of

Theosophical beliefs in

Ulysses ("One could even argue

that this model of memory underlies a complex textual memory in

the novel..."). No matter whether a Universal Memory exists in

nature: it offers one way of describing a striking literary

effect.

The sense of retrospective totality achieved by this recycling

of old elements does not end with the last page of

Circe.

Ithaca builds on it by subjecting countless details

encountered earlier in the book to a catechetical logical

examination that feels comprehensive, as if they are

contributing to some vast Aquinian summa. At the opposite

stylistic extreme—concrete, emotional, associative—

Penelope

achieves a similiar feeling of wholeness by revisiting the day's

events through the swirling and intersecting mental orbits of

one woman's reflections. The sense of totality begins in the

vast historical sweep of

Oxen of the Sun, and with the

exception of

Eumaeus persists to the end of the novel.

Ulysses

is not simply the record of one day. It is an encapsulation of

human existence that teaches its readers how to hold it in

memory, a unified interpenetrating whole.